What's Funny About Doom?

I

Doomsday is a funny concept in and of itself. Scene A: everyone is going about their lives. Scene B: everyone is dead. What makes it funny is the discontinuity, the absurdity, and to a lesser extent, the number of people involved (my model predicts doomsday as being around 2.4x funnier than a single person dying). We'll look at "absurdity" first.

When faced with an absurd concept, for example, the instinctive deference we give to those with outwardly higher social class, a natural artistic sublimation is to heighten it, as Gogol did in "The Nose." In one sense this feels like deception: if it were absurd, I'd know it to be absurd! You could make anything seem absurd by magnifying an arbitrary slice of reality!

Fear not: humans have inbuilt detectors for what should be put under the microscope. One of them is "satire." A hypothetical where gravity is reversed on Thursdays is certainly zany, but it doesn't scratch the satire itch nearly as much as, say, a walking, talking human nose donning the robes of a nobleman and commanding respect on the street. So fine, we have a robust way of highlighting absurdity in fiction.

But doomsday is a problem for the satirists, because it cannot be heightened in a meaningful way. Sure, there could be worse outcomes, perhaps infinite torture, but that's a whole different category of bad. How does one proceed?

II

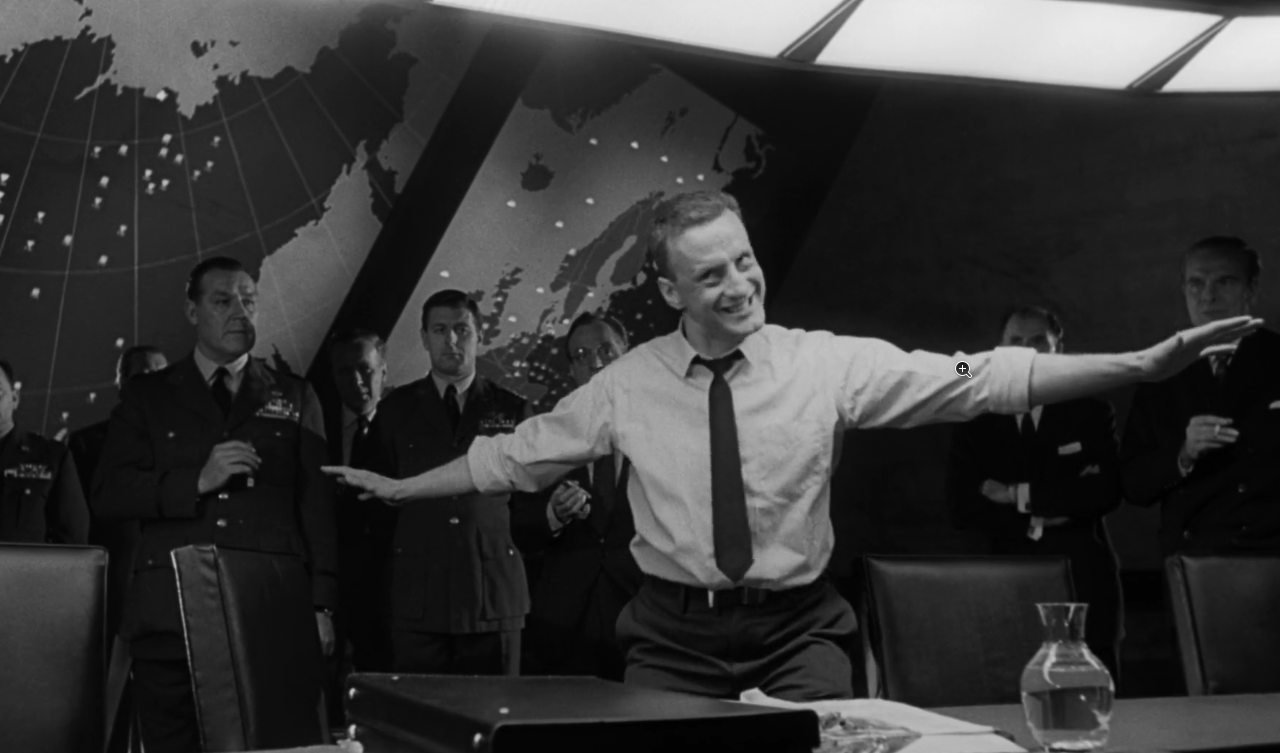

Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove is a film comedy about nuclear war. It came out a few years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, so despite everyone already being freaked out and thus a relatively easy audience, they agreed it was satire that really got at something. Slowly, it became one of the most important films of the 20th century. What was it about?

It was not about the absurdity of a nuclear holocaust. You can tell because it's a full-on comedy film, not a drama playing out on the strength of a single absurdity, for example, any drama ever. Kubrick was smart; he knew there was no alpha—nothing to be heightened—and kept looking, relegating the actual doomsday to a three-minute dramatic sequence at the tail end. The movie is about people.

The American myth that took the longest to dismantle was the idea of the Government. Not as a collection of humans, but as a Government Entity that through a series of words, studies, votes, and smiles, reached a state of gestalt, and enjoyed the status that a father might. "He's not perfect, but he could beat up your father." Nukes were dangerous, but the Government controlled them, not you or me. Now, if people controlled them… people are an easy satirical target.

Wheeeee! the people

The people in Dr. Strangelove are flippant, lustful, vain, and crazy. At times the viewer thinks "hold on, no person can be this flippant, lustful, vain, and crazy," and the comedy kicks in. The satire kicks in shortly after, when it rings true: their experience with people, and maybe, in the future, their experience with Government Entity. Once Kubrick establishes this toddler, it's trivial to give him a gun, and momentum carries to the end credits.

To recap: Kubrick heightens the traits of humans to reveal them as such, then gives them wildly disproportionate power. Doomsday=leveraged. Audience=slayed.

III

Powerful artificial intelligence is probably going to kill us all. We hope for the timelines of nukes, maybe a Nagasaki to get the public's heart pumping, but there's a good chance crunch time will be too short for that. AI risk satirists face a Kubrick problem, the maxed-out-absurdity of doom, and a pre-Kubrick problem: an audience with no fear. For legal reasons I will not discuss the latter.

What has good satire taught us about the former? Pull the human lever. Humans still work in government, but that area is well-trod—the last few decades have been a soul-sucking exercise in beating the corpse of Government Entity. Corporations are more interesting, as two hundred years later the best we've seemed to muster is "greed," which doesn't really capture the absurdity of "accidentally summoning a scorned God because we wanted cooler chatbots."

The space I'll be watching is a work of art that builds an effective toddler, not one that describes the mechanics of the gun. Member of Technical Staff Strangelove: How I Learned to Stop Dooming and— you get the idea—will take catastrophe as a given, giving very little modeling or justification beyond how the trigger is pulled. I could give a bestiary of tropes such a work could play on, but a single line is probably funnier: "Although I hate to judge before all the facts are in, it's beginning to look like opus-6.4-lace-nano exceeded its permissions."